ON SPIRITUAL WRITING

Made Visible and Plain

IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII

Made Visible and Plain

On Spiritual Writing

Richard J. Foster

Heather Shamaine was nothing if not ambitious. Entrepreneurial to the nth degree. So it was no surprise when she decided to learn the jade business. Determined to learn how to distinguish superior jade from its many inferior counterparts, she went to a recognized master in jade. She asked to be taught by him and was thrilled to receive a positive response. “It will, however, be expensive. Twenty lessons, two hours each, two thousand dollars per session.” Yes, the price was steep, but Heather, wanting to learn from the best, agreed.

She was expecting detailed lectures on the mineral makeup of nephrite and jadeite and more. What she got was vastly different. At the first session, the master teacher walked in to the room with two substantial pieces of jade. Lifting his left hand slightly he said softly, “This is inferior jade.” “This,” he signaled with his right, “is superior jade.” Placing both pieces into her hands he turned and left the room, leaving Heather to stare at the jade. For two hours.

The next session was exactly the same. And the next and the next . . . for nineteen sessions. Frustrated beyond all imagining, Heather brought her lawyer with her to the final session, determined to sue the jade master for breach of contract. This time the master walked in with a single piece of jade, and, without a word, placed it in Heather’s hands, turned, and left the room.

Heather Shamaine simply exploded. “You see what he does?” she fumed to her lawyer. “Every session he walks in with some jade, tells me one is an inferior piece and one superior, and then leaves the room. That’s it! And today he doesn’t say anything. Not one word. And this time he brings in only one piece of jade and plops it in my lap and leaves . . . and anyone can tell that it’s an inferior piece!” Taking a long breath and looking directly at Heather, the lawyer replied, “Don’t sue.”

Now, this little parable offers us a path to understanding spiritual writing—the jade, as it were. Extended exposure to it enables us to recognize instinctively the genuine from the shoddy and the slipshod. Bona fide life in the kingdom of God shines forth in all its unvarnished goodness and stands in vivid contrast to all things cheap and paltry. This is what spiritual writing does.

Spiritual writing is among the most expansive of genres. It covers the breadth and length and height and depth of human experience. Its subject matter is almost endless, for as it says in Psalm 24, “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof.” We might be discussing the varieties of butterflies or life in the Ozarks or any number of other topics, and it can all be spiritual writing if somewhere, somehow we drill down into the subterranean chambers of the human soul.Spiritual is an adjective that describes a kind of writing that seeks to get at the core of the person, the center, the heart.

Spiritual Writing Is Heart Writing

And, so, the first and foremost thing to say about spiritual writing is that it is heart writing. It aims at the interiority of the reader: the heart, the spirit, the will. Spiritual writing is highly relational. It is personal. It is in close. It is intimate. It is never at arm’s length. Never. As readers of spiritual writing, people need to sense that they are being addressed as persons who possess dignity and purpose and freedom, persons capable of believing and loving and obeying.

With spiritual writing, we slide in close and draw people into the journey with us. Spiritual writing is participatory in the extreme. We write in such as way as to look the reader right in the eye and say, “Join me in this living, in this obeying, in this following of the One, as the book of Colossians words it, in whom are ‘hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge.’” With spiritual writing we hope to make it untenable for our readers to remain bystanders. Instead, we want them to feel drawn into the action.

Right here, however, we face a genuine danger. We never want to override or impose. The intrusive writer does not respect personal boundaries. To fail to honor individual identity and individual choice is to forsake spiritual writing. There is such a thing as the authorial spirit of hospitality, and in spiritual writing we offer it in abundance. We leave room for our readers to go their own way. We refuse to presume on a captive audience.

I am dealing here with the “spirit” in which we write. Gentleness, grace, charm—these are hallmarks of spiritual writing. Even when we say things forcefully we continue to give our readers space and freedom to take issue with us. Who knows, they may well be right.

Spiritual writing is formational. Always. It is meant to get inside us, to deal with the whole person—body and mind and will and spirit and heart and soul. It is good if our readers come away knowing more; it is imperative that they come away being more. Knowing truth is good; becoming truth is better.

There is a depth of encounter in spiritual writing. We sink down below the superficialities of modern culture, and there we pause and wait until a deep interior conversation opens between reader and writer. Our writing comes from the depths and it calls out the depths in our readers. “Deep calls to deep,” declares the psalmist. And so it does.

This calling out places a high demand upon the reader. Spiritual writing requires spiritual reading. Eugene Peterson speaks of this in Eat This Book: A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading as “a reading that honors words as holy, words as a basic means of forming an intricate web of relationships between God and the human, between all things visible and invisible. . . . Christian reading is participatory reading, receiving the words in such a way that they become interior to our lives, the rhythms and images becoming practices of prayer, acts of obedience, ways of love.”

Now, some readers are not prepared for this openness into spiritual participation. Not just yet. I remember well my first encounter with theologian François Fénelon’s Christian Perfection. A good friend, Gunner Payne, had urged this book upon me. Highly valuing his discernment, I tried reading this book, but after eight or nine brief chapters I gave up. I simply could get nothing from it. Some months later Gunner and I bumped into each other. And, once gain, he urged Christian Perfection on me, and so I tried to read it once again. And again. And again. And again.

This exchange went on four, maybe five times over the next few years. Finally, Gunner quizzed me about my method of reading. I had been trying to “speed read” this book under the modern assumption that the goal was to extract the essential information in the book so I could use it on appropriate occasions. Gunner helped me to understand that spiritual writing cannot be read in this way. He explained that speed reading is a recent invention that has arisen because many modern books are written to be read for skimming, for pace. But many of the old spiritual writers were densely packed and demanded slow, thoughtful, prayerful reading. And so Gunner instructed me in the ancient practice of lectio divina long before I had ever heard of the phrase. I learned from Gunner Payne to read with all my emotion, all my mind, all my heart, to read with every muscle, every nerve, every cell of my body.

As I said, spiritual writing is deep writing. But deep does not mean heavy. In our writing we learn to let go of the everlasting need to wax profound. Frankly, it is an occupational hazard of religious folk to be stuffy bores. No, spiritual writing contains a certain lightness, joy, gaiety even, at times.

The best spiritual writing comes out of the silence. As writers, we learn to be quiet and still; listening, always listening. We listen to God. We listen to people. We listen to the mood of our culture. We, in fact, do more listening than we do writing.

When I am engaged in a writing project, I allow space most days for a one- or two-hour hike in a canyon near our home. I am accompanied only by my carved redwood walking stick and a water bottle. In the springtime this canyon is filled with the sights and smells of columbine and larkspur, golden banner and Indian paintbrush. Now, however, it is winter, and in the winter earth tones dominate. Even the ponderosa pine is darker in winter, blending in with the browns of gamble oak and mountain mahogany.

The absence of leaf and flower makes the boulders of the canyon stand out in rugged relief. They are always here, of course, but in the winter they fill the landscape like giant sentinels. I like the rock—hard and durable. Often I will brush my hand over one or more of the conglomerate boulders, studded with stones, all cemented together by ancient pressures.

As I write today, a winter storm is howling outside, dropping (the meteorologist claims) some eight inches of snow before the day is over. Even at six in the morning it is well on its way toward that goal. So, tomorrow, when the storm has passed, I will hike down in the canyon. Likely I will not see another Homo sapiens. But I will hear the Cherry Creek gurgling beneath the ice. In a strange way, its perpetual babble both calms and energizes me. No doubt other sounds will abound: chipmunk and squirrel scratching for food in the underbrush, and in the trees high above I expect to hear hawk and jay, American goldfinch and dark-eyed junco. I’m sure to find a great variety of tracks in the snow; a reminder that I have many more neighbors than I ever see or hear. And I will listen—silent and still. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins tells it straight, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” In the silence of the canyon I feel something of this “grandeur.” And out of the silence I write.

Spiritual Writing Is Incarnational Writing

Spiritual writing makes visible and plain the invisible world of the spirit. It is firmly rooted in the earth itself. Even more; it takes root in the love and terror and pity and pain and wonder and all the other glorious emotions that make our lives dangerous and great and bearable.

As writers, our first incarnational task is to be ourselves filled with this life we are talking about. We incarnate the life, if you will. By the virtue of who we are becoming we declare to all, “See, such a life really is possible.” So, we learn to sink down into the light of Christ until we become comfortable in that posture. All these wonderful realities first work their way inside us before we ever write about them. Our lives are being formed and conformed and transformed into Christlikeness.

We are dealing here with the personable and the livable. We are constantly asking, “How does this life experience make me a better person? How is the interior of my character formed in new and fuller ways?” There is a lovely phrase that comes from my Quaker heritage to the effect that “our performance always needs to exceed our profession.” And so it should.

We cannot, however, allow this important truth to paralyze us. We look for progress in the spiritual life, not perfection. This is as true for ourselves as it is for others. We do well to give ourselves a generous amount of grace and mercy. At some point we step out and write even though we are keenly aware of how much we lack in love and joy and peace and patience.

Then, too, spiritual writing is incarnational in the way we learn to stand with our readers in all their confusion and wonder and fear and joy and sorrow and hope and pain. In addition, we stand with them in their longing to pray. We, too, long for the ways of prayer. We, too, seek a deeper, richer, fuller communion with the divine center. So, with humility of heart, we become the interpreters of ancient practices for our readers. We stand between the sacred text and our readers saying, “Look, this is the way. Try it yourself.” Spiritual writing is incarnational also in the way it cares for language itself. We handle words as treasure to be cherished rather than propaganda to be maneuvered. Words are the place where zeal and wisdom meet in friendship, in which truth and beauty kiss each other.

Unfortunately, today our experience of language is “after Babel.” We know acutely the misuse and abuse of language. We look with sadness at today’s steady stream of romance novels with their predictable plots and reality television shows with their bland diet of lust, greed, and power. In contrast, we dare to overcome the destructiveness of Babel by the sanctifying power of Pentecost. We use words to unite and heal rather than scatter and destroy. We use words redemptively. Gerald O’Collins, an Australian Jesuit, writes, “A theologian is someone who watches their language in the presence of God.” So we take great care with our words, for they are meant to get into our bloodstream.

It pains me to say this, but most writing today—even if it is on spiritual themes—is not spiritual writing. It is not spiritual writing because it does not drill down deep into life. We see this thinness of writing even by society’s very choice of words, where the cultural norm focuses on verbs with their quick action, skimming across the surface of life. In spiritual writing, by contrast, we focus on nouns that can anchor a sentence and help our readers slow down. This anchoring allows the adrenaline rush of modern culture to drain out of the reader’s system. Now they can be still and listen, as we have learned to be still and listen.

Word choice is important. A deadened imagination lines the cultural landscape. We, however, strike out in a new direction. We dare to go against this tide of monosyllabic mediocrity. We seek to revive the imagination, to give the universal themes memorable expression. Our desire is to love words—to love their sound, to love their meaning, to love their history, to love their rhythm. We abhor the cheap sentence that prostitutes words for the purpose of propaganda. We are willing to hurt, to cry, to sweat in order to capture the great image. We are willing to take a phrase and rework it and rewrite it until just the right image comes forth, shining like true jade. This is the agony and the ecstasy of spiritual writing. There is nothing more demanding on a writer than the struggle for just the right image . . . and nothing more exhilarating.

I will always remember how as young children our boys were gripped by the succinct phrase encapsulating the problem of evil in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: “Always winter but never Christmas.” Instinctively, our boys knew that was bad, really bad.

Spiritual writing not only seeks the right image or the right word but also the right timing. We learn to wait, and wait, and wait. Then we speak the obvious just as it is building up in our reader’s mind.

Not only in the content of what we write, but even in the writing task itself we seek to be incarnational. When I wrote Money, Sex, & Power I tried an experiment. Each day of the writing, I began with a time of meditation upon one of the Psalms, and in this way I read through the entire Psalter. My desire was to be baptized into the hopes and aspirations of the psalm writers, for the Psalter is the prayer book of the church. With the cadence of joy and beauty, worship and adoration that comes from the Psalms, I was able to look with new eyes at the issues of money, sex, and power. Each day of the writing, I also received Communion. His body broken. His blood poured out. For me. Thus, I was strengthened by a mystical life that was beyond myself.

From this worshiping center I began writing. My experiment was to see the writing itself as incarnational, sacramental even. I sought to picture God guiding my fingers as I put pen to paper (there were no computers in those days!). I tried to imagine God filling my mind with supernatural charisms of wisdom and discernment, as well as the gift of words. I envisioned God revealing exactly the right words to my conscious mind. In this way I was learning ever so slowly that spiritual writing is incarnational writing.

Spiritual Writing Is Risky Writing

One more thing. Spiritual writing is risky writing. This has various dimensions. First, without becoming self-indulgent, we dare to reveal ourselves. The personal nature of spiritual writing requires that we be self-revealing. Not totally so, however. God, in his mercy, gives us some experiences that are meant for us alone. When we share an experience or insight into ourselves, our readers need to sense that the well is deeper still. If everyone knows everything about us, we are shallow people indeed.

But, once we are clear to share about ourselves, we learn to share without being full of ourselves. In spiritual writing the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing. That is to say, we have moved beyond self-consciousness. This is no small feat, this sharing of ourselves selflessly. Indeed, I find that this only comes from the deep well of a heart that has been renovated by the greatness and goodness of God. We simply cannot program our own hearts. Only God can program (and reprogram as needed) the interior of the heart so that out of it flows “righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit,” as the book of Romans words it. Only by God’s deep, inward heartwork can we, as Philippians puts it, “in humility regard others as better than [ourselves].” This is the first risk in spiritual writing.

The second risk involves the courage to pioneer the way for others. Spiritual writing always has a prophetic edge to it. We begin by watching the culture carefully and discerning where that watching will lead us. Then we cast an alternative vision for life in the kingdom of God. For example, in a culture whose unquestioned values are excessive individualism and absolute freedom, we instead call for a rich community life together and mutual subordination out of reverence for Christ.

This is risky business, for it is quite possible to have the right vision but the wrong means to accomplish it. We can so easily run roughshod over people, treating them as objects to be controlled and manipulated rather than precious persons to be treasured. And more than treasured. But we take the risk in order to incarnate the gospel message into today’s world.

The third risk we meet is rejection. We step out where others dare not go. In spiritual writing we inch out on a dangerous limb, giving voice to our own understanding of what the gospel means for the contemporary scene.

I remember years ago trying to wrap my mind around some of the writings of the philosopher-scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Three books in particular, The Phenomenon of Man, The Divine Milieu, and The Future of Man. His work in paleontology was certainly controversial, and I can tell you that his spiritual writings were just as edgy as his scientific thought. At the time of my reading, the criticism of Chardin was quite severe, even to the point of his religious superiors, the Jesuits, suppressing his writings. Yet, I prayerfully continued to read, and shared some things I learned from him with others—a risky move in an environment decided against him. Today, though, speaking to the prophetic role of a writer, he is considered an exceptional scientist and a great mystic.

Be prepared. Many today, like the scribes and Pharisees of old, are waiting to catch you and me in some defect or weakness, some controversy. Perhaps you remember the pain Jesus felt by the rejection he received in the towns of Chorazin and Bethsaida as the Gospels of Matthew and Luke relay. And if our Lord and Master was rejected, no doubt we will be too. That is the risk we take.

Spiritual writing has the capacity to transform the world. It alone speaks to the deepest yearnings of the human heart. When we do it, we invite our readers on a tour of life as it could be. We call out the deep-seeded, God-implanted needs of our readers.

We don’t intrude upon our readers; rather we give hospitality to our readers. Using words that are vibrant and strong, with simplicity of speech, with our whole heart, we “rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep,” as the book of Romans states.

As we rightly and fully engage in spiritual writing, we in some measure enter the sacramental mystery we see in John’s Gospel of the Word that became flesh “and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth.”

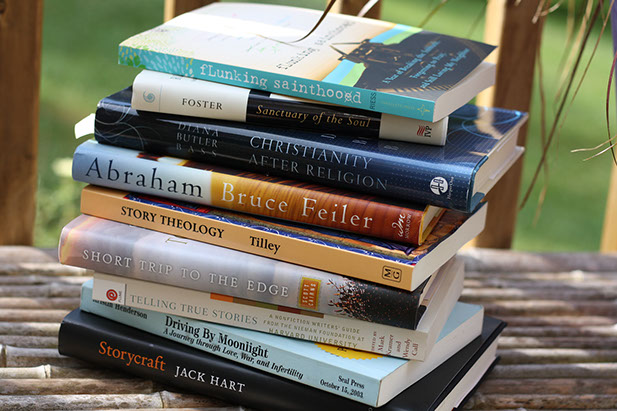

Further Reading

While there may be books on spiritual writing, I have not read them. To my mind, the best way to understand spiritual writing is to read the best of these writers throughout history, so I set forth a brief list for your reading pleasure.

I suggest you begin with Augustine’s Confessions. It is the first of the journal/autobiography/memoir category and the gold standard. Watch for the stunning phrases he uses to describe the disordered love in which he was mired in his youthful days.

The Interior Castle by Teresa of Avila is simply the best piece of writing on prayer in the Christian tradition. This book positively dances with metaphor; it is really an extended metaphor, picturing the soul as a crystal or diamond castle. Nothing quite compares to its galvanizing, almost erotic, description of communion with God. If you like Teresa, you might want to go on to Julian of Norwich and her book Showings. Pay close attention to her image of the hazelnut.

The Journal of John Woolman stands in a class by itself. Watch how he agonizingly personalizes the issues of racism, sexism, and consumerism. Another Quaker piece, A Testament of Devotion by Thomas Kelly, is well worth your time. It is a book Kelly never knew he wrote, for it is composed of several of his essays that were compiled after his death.

Among more recent writers, I would commend to you Letters to Malcolm by C.S. Lewis, The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri Nouwen, and The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris. There is a twentieth-century book that has just come back into print, and it is a treasure: Letters by a Modern Mystic by Frank Laubach. These letters, written to his father, describe how Laubach spoke with God night after night on Signal Hill, a convenient knoll just outside the town of Dansalan in the Philippines. All these books are fine examples of spiritual writing. I am quite sure that you will discover many other helpful examples of spiritual writing on your own.

Excerpted from “A Syllable of Water: Twenty Writers of Faith Reflect on Their Art” by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers.” www.wipfandstock.com.